There are three caddisfly case-makers that we commonly see in the winter that make their cases of pebbles and sand and can be confused: Apataniidae (little mountain case-makers), Goeridae (weighted case-makers), and Uenoidae (little northern case-makers). Case size is similar with the Goerids and the Uenoids; Apataniids tend to be a little bit smaller. (That's a little Apataniid in the photo at the top of the page side-by-side with the much larger "humpless case-maker" --

Brachycentrus appalachia.) But we can normally tell them apart by 1) looking at the cases as the larvae crawl around in our trays, and 2) anatomical analysis -- i.e. microscope work in the lab.

A. The external view (i.e. what we see when we look down at the case)1.

Apataniidae (

Apatania incerta is the most common species we see in our streams). The Apataniid case is composed of very small pebbles/grains of sand and is commonly cornucopia shaped.

It has a "hood" at the top of the case that covers the head of the larva.

That means when you look down on the top of the case, you might see some legs sticking out the sides of the case, but you won't see the head of the larva. It's very odd to see that case crawling around on its own!

One other thing, if you flip the case over, the larva might peek out, in which case you'll note that the body is yellow.

_________________

2.

Goeridae (

Goera fuscula,

Goera calcarata). The Goerid case is easily recognized by the fact that there are 2 large, ballast stones on each of its sides. In the center of the case you'll see smaller pebbles.

If the case is inhabited, you

will see the head of the larva as it crawls around in your tray. But you may have to give it some time: Goerids seem to be hesitant to stick out those heads. One other thing you can see that's important: there are long projections on the sides of the head. More on those in a minute.

3.

Uenoidae (to date, we've seen 5 or 6 species:

Neophylax oligius,

Neophylax consimilis,

Neophylax mitchelli,

Neophylax aniqua,

Neophylax concinnus, and possibly

Neophylax toshioi. Like the Goerids, Uenoids place larger stones on both sides of their cases for weight -- but they normally have 3-4.

and one of my all time favorites

The largest stones are often placed at the front of the case -- as we can see in all of these photos, and

dramatically in the photo below.

Uenoids, like the Goerids, stick out their heads as they move in your tray, but you will not see projections by the side of the head.

________________

B. The internal view (i.e. key larval anatomical features.) (Things you'll want to know if you work at ID in a lab.)

1.

Apataniidae. The leading edge of the sclerites on the mesonotum is straight -- no indentations and there are no sclerites at the front of the metanotum (sa1). Rather, in that position, there is a transverse row of setae.

2.

Goeridae. The mesonotum on the Goerid has two pairs of sclerites -- not just one -- and to the side of the mesonotum are those long projections we can see when we look down at the live insect -- the mesepisterna. Moreover, there

are sclerites on the metanotum -- 3-4 pairs depending on the species. The pronotum is very broad with sharply pointed anterolateral projections. (The first photo below was taken by a friend and used with her permission.)

3.

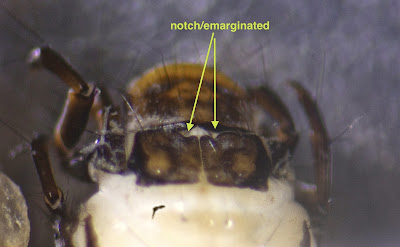

Uenoidae. One pair of mesonotal sclerites, like the Apataniids. But, the leading edge of the mesonotum is "emarginated," or notched, not straight across.

In addition, and again in contrast to Apataniids, Uenoids

do have sa1 sclerites on the metanontum.

One other feature to look for on the Uenoids. If you look at the underside of the head you will see that the ventral apotome is "T-shaped."

_________________

There is, of course, a "fourth" case-maker that we see in the winter that makes its case out of pebbles -- the Glossosomatidae, "saddle case-maker." Here the case is shaped like a dome...

You will probably not see the head of the larva as the case moves in your tray. But if you flip the case on its back, there's a good chance the larva will crawl out of its case -- something I've never seen with Apataniids, Goerids, or Uenoids. You'll also see that the case has openings at both of its ends with a "saddle" in-between.

And, with the genus

Glossosoma -- the only genus I've seen -- the key diagnostic features can be seen without using magnification.

1. The meso and metanota are completely fleshy without any sclerites, and there are no "humps" -- lateral or dorsal -- on abdominal segment 1.

2. There is a dorsal sclerite on abdominal segment 9.

3. And the anal prolegs appear to be short and "stubby" since the bottom half of those legs are fused with segment 9.

_______________________

Once more on those cases.

1. Apataniidae

2. Goeridae

3. Uenoidae

4. Glossosomatidae

________________

All four are found in the same places: on the tops of rocks or on the sides of rocks. But the Goerids don't hold on very tightly.